Cause Coniferiporia sulphurascens is a native root pathogen and often found in forested areas, in large old tree stumps where it can live several decades as a saprophyte. Infection spreads from tree to tree through the stand and from stumps to roots of healthy seedlings or trees that contact infected wood. Root infections eventually lead to root and lower bole decay; the tree dies directly or as a result of windthrow. Infected trees may take several years to die, declining slowly over time. Trees are infected and killed regardless of individual vigor. Mortality increases steadily in Douglas-fir stands 30- to 150-years old but spread is slower in older stands and it takes many decades for the large old trees to be killed by the fungus. Thinning stands to decrease root contacts has been suggested for disease management in the past but was found not to be helpful.

This is the most serious disease of Douglas-fir and true fir. Douglas-fir, mountain hemlock, grand fir, Pacific silver fir, and white fir are the most susceptible. Western hemlock, western larch, and spruces are often infected but usually not killed. Western red cedar and pines are resistant as they rarely become infected and rarely die as a result of infection. The disease is found from the Klamath Mountains of northern California to near the northern limit of Douglas-fir in British Columbia, and east to Idaho. Bark beetles are often present in these trees.

Laminated root and butt rot of western red cedar is caused by Coniferiporia weirii (formerly Phellinus weirii).

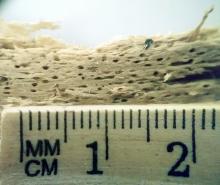

Symptoms Crown symptoms may not become noticeable until 50% or more of the roots system has been destroyed. Reduced terminal growth is usually the first crown symptom. In the later stages of root infection, affected trees show crown yellowing as well as reduced terminal and lateral branch growth. Basal resinosis or pitching (large exudations of pitch at the base of the stem at or below the root collar) may also occur. Decay appears as reddish-brown-to-chocolate-brown irregular patches or crescent-shaped stains, usually in the heartwood, on fresh cut stump, or root cross sections. The stains on the stumps can fade away within a few days of the trees being cut. This is especially true for stumps that get full sun. Small oval pits (ranging from 0.5 to 1 mm in length) appear in advanced decay. Diseased trees often fall over because most roots have decayed. White to gray pathogen mycelium often covers infected roots. Decayed wood separates at the annual rings like pages in a book; hence the common name laminated root rot. Diagnostic small red to brown fungal hairs called setal hyphae, which are diagnostic for this fungus, often cover the laminated rot. Clumps of the setal hyphae may be seen with the naked eye but a hand lens will be more helpful where individual setal hyphae will look like reddish-brown whiskers. Flattened conks develop on the undersides of roots or logs.

Cultural control

- Avoid building near centers of root-rot infection. Construction activity usually worsens the situation and can lead to tree failures and property loss.

- Remove healthy appearing trees that are next to confirmed infected trees in the landscape, as these are likely to be infected as well. This will reduce root-to-root spread to other trees that are not yet infected.

- In mixed-species areas, favor resistant species such as cedar, pine, or hardwoods when planting, thinning, or harvesting.

- Excavating infected stumps has helped on industrial land.

- Avoid planting highly susceptible hosts within 50 feet of infested sites.

Reference Hansen, E.M., and Goheen, E.M. 2000. Phellinus weirii and other native root pathogens as determinants of forest structure and process in western North America. Annual review of phytopathology 38:515-539.

Wallis, G.W. and Reynolds, G. 1965. The initiation and spread of Poria weirii root rot of Douglas fir. Canadian Journal of Botany. 43:1-9.